For years, mobile malware was treated as a noisy, almost secondary problem. Banking trojans appeared, stole credentials, got detected, and disappeared. Security teams focused on endpoints, servers, and cloud identities, while smartphones remained the uncomfortable blind spot between personal and corporate risk.

That era is over.

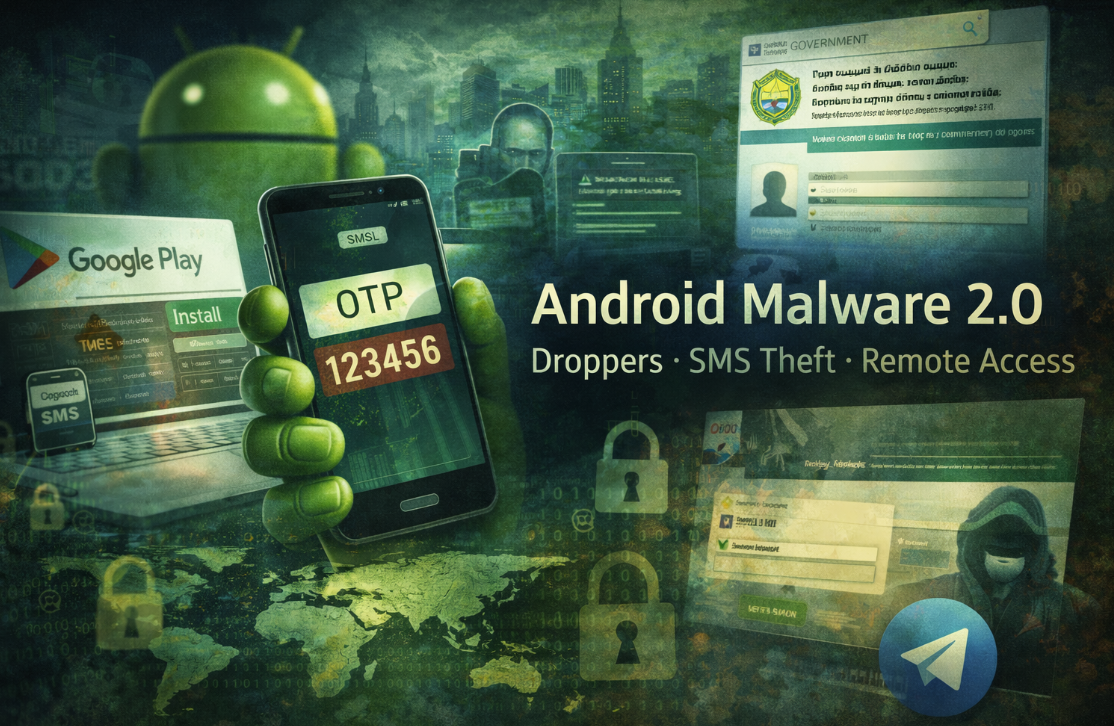

What we are witnessing today is not simply “new Android malware”, but the professionalization of mobile cybercrime. Android threats have evolved into modular, scalable platforms that rival ransomware ecosystems in both maturity and efficiency. These are no longer opportunistic scams. They are industrial operations designed to bypass authentication, hijack identities, and quietly monetize trust at scale.

From Simple Trojans to Invisible Droppers

Early Android malware relied on direct installation: a malicious APK was installed and immediately began its activity. That approach was effective, until defenses improved.

Today’s attackers prefer a subtler path. Instead of shipping malware directly, they deploy dropper applications that appear benign. On the surface, these apps look like updates, media files, invitations, or even trusted platform components. Beneath that surface lies an encrypted payload, dormant until installation is complete.

What makes this shift dangerous is not just obfuscation, but self-sufficiency. These droppers can unpack and activate their malicious components locally, without reaching out to external servers during installation. Traditional security checks see a harmless app; the malicious behavior only emerges later, once trust has already been granted.

This architectural change marks a fundamental evolution: malware is no longer an app it is a process.

MS Theft as a Weapon Against MFA

At the core of many modern Android campaigns lies one objective: control the second factor.

SMS interception was once a side capability. Today, it is the primary business model. By stealing one-time passwords, attackers bypass the very mechanisms organizations rely on to protect email, banking, cloud services, and messaging platforms.

Once installed, modern Android malware can silently read incoming messages, suppress notifications, and even send SMS messages autonomously. This allows attackers to move laterally, infect contacts, and maintain control without raising suspicion. In some cases, devices can execute real-time USSD commands, transforming a smartphone into a remote-controlled fraud terminal.

From a CISO perspective, this is the uncomfortable truth: SMS-based MFA is no longer a safety net; it is a liability.

Messaging Platforms as Command Centers

One of the most striking developments is the operational use of Telegram. What began as a secure messaging app has become an unofficial backbone of cybercrime logistics.

Attackers use Telegram not only to coordinate campaigns, but to generate malware builds, distribute payloads, and manage infected devices. Automated bots assemble unique APKs, each tied to separate command-and-control infrastructure, ensuring that takedowns remain localized and ineffective.

Even more troubling is the abuse of stolen Telegram sessions. Once a device is compromised, attackers hijack existing accounts and use them to distribute malware to trusted contacts. Infection spreads not through spam, but through social trust.

Malware Without Developers

Perhaps the most dangerous shift is economic rather than technical.

Android malware is increasingly sold as a service. Subscription-based tools, one-click APK builders, and preconfigured control panels allow individuals with minimal technical skills to launch sophisticated mobile campaigns. Some platforms even allow attackers to browse the catalogue of Google Play and wrap malicious payloads inside legitimate applications.

This removes the last barrier to entry. Mobile cybercrime no longer requires expertise: only intent and funding.

As a result, attack volume increases not because malware is better, but because more people can deploy it.

Weaponizing Trust: Government, Courts, and Institutions

Another defining feature of recent Android campaigns is the deliberate abuse of institutional trust. Fake government portals, court notifications, and public service websites are used to lure victims into installing malicious apps under the guise of compliance or urgency.

This tactic is brutally effective. Users are conditioned to trust authority. When an app claims to be a legal notice or a state service update, skepticism disappears. Security controls relying on user judgment collapse instantly.

For organizations, this matters because executives and employees are not immune. The same mechanisms used against citizens are used against board members, finance teams, and senior leadership.

Why CISOs Can No Longer Ignore Mobile Risk

The smartphone has become the primary identity broker of the digital world. It receives authentication codes, hosts messaging apps, stores credentials, and confirms transactions. Compromise the phone, and the attacker no longer needs to breach the enterprise perimeter; they simply log in as the user.

A single infected device can enable:

- MFA bypass for corporate email

- Cloud session hijacking

- Executive impersonation

- Fraudulent approvals

- Silent persistence across multiple platforms

This is not a mobile problem. It is an identity problem.

A Strategic Inflection Point

Android malware has reached a level of maturity that demands a strategic response. Its operators behave like enterprises. Its infrastructure is resilient. Its tooling is commercialized. Its impact extends far beyond the device itself.

For CISOs, the message is clear: mobile security can no longer be treated as a subset of endpoint security or left to MDM defaults. It must be integrated into identity protection, fraud detection, and executive risk management.

The attackers have already adapted. The question is whether defenders will do the same, before mobile compromise becomes the most common entry point into the enterprise.